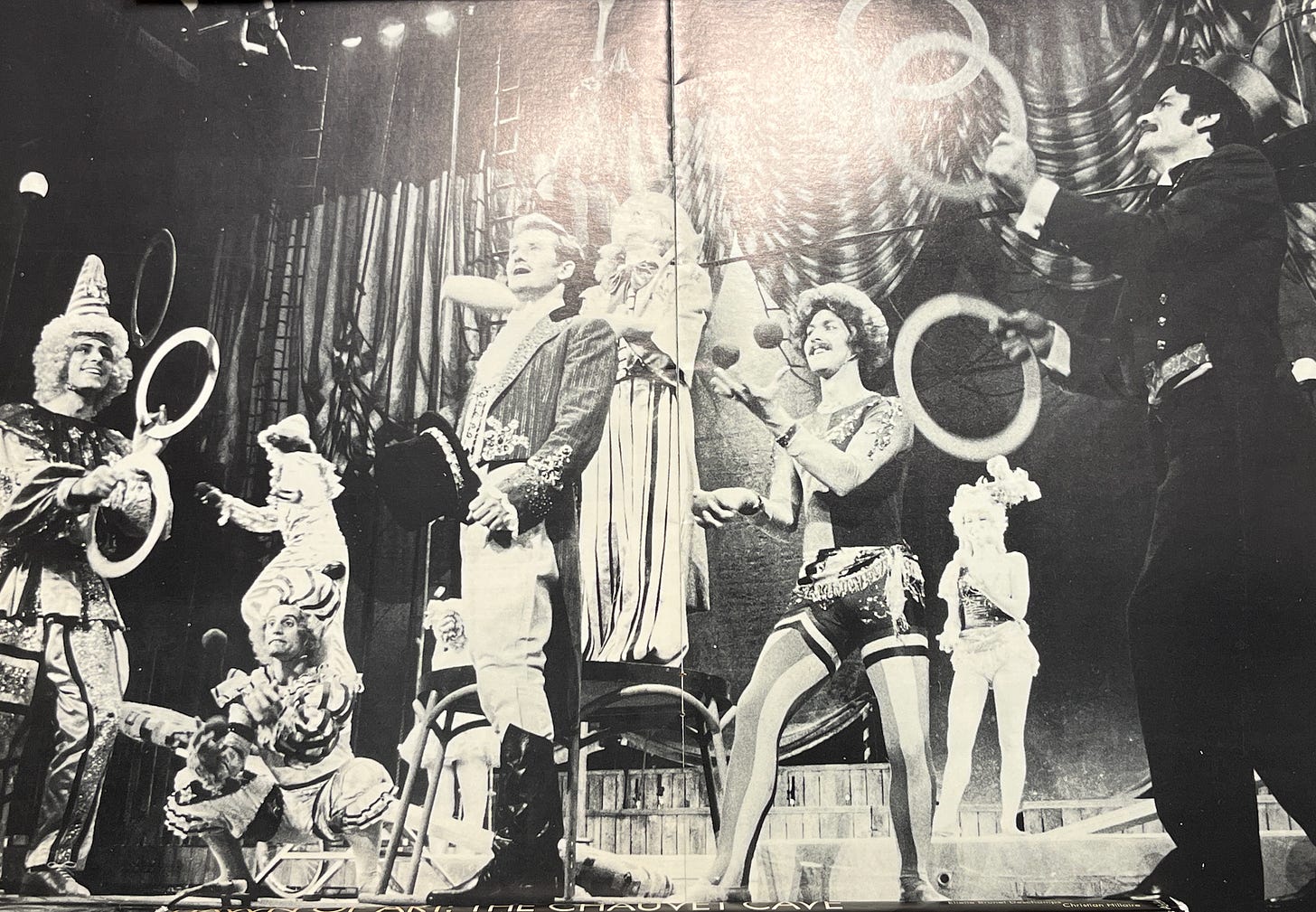

My First Time On Stage as a Professional Actor

It did not go as planned

If you’ve been subscribed to Honestly Human for a while you probably like engaging with personal stories. I’ve shared more than one-hundred and thirty original stories so far in this publication. Many of you would argue with me if I suggested that you have just as many stories to tell. Most people w…