The Graveyard and the Tennis Ball

Family history is an expression of love

I was seated at the dining room table with my parents. Coffee and a spiced holiday tea made by my wife plumed rising steam over a pile of family photos, birth certificates, old phone records, love notes, and Christmas cards—some of which were a century old. We’d unearthed them from a remote closet during my parents’ last move, but my mother’s brow twisted in distress.

“Mom,” I said. “It’s okay. This is not a test. You don’t have to recall anything in particular. If something comes up, that’s great, but it’s no problem if you can’t remember any details.”

I had invited them to arrive hours before the start of our extended family Christmas dinner so I could ask them some questions about our family history.

At age ninety my father’s recall of his life experience remains surprisingly stable, though subject to the usual loss of detail that comes with time. My mother turned eighty-eight in May. Her dementia leaves her vacillating between an easy recall of history and a more frequent, alarming blankness of fact.

Multiple generations of my family, as far back as I knew, were settlers in New England. I myself was born in Connecticut, but my parents left when I was two years old and drove across the country to Oregon where my father would complete his master’s degree.

We never went back.

I remember my mother telling me years ago how bonded I was to my grandparents as a toddler. It was my grandmother Elizabeth Crouch, Betty as we called her, who cared for me in the first weeks when my mother contracted sepsis in the hospital. I saw them on a daily basis in those first years of my life.

My mother recalls the scene of saying goodbye to her parents Betty and Everette at the curb, our car packed for the trans American move, and me brightly saying, “See ya in the morning!” The innocence and joy of my connection, along with the fact that I had no way of knowing there wouldn’t be another visit with them in the foreseeable future, was more than my mom could bear. She cried through all ten states on the journey west.

Leaving generations of New England descendants we made this shift toward an independent, non-familial orientation in the formative years of my family and I’ve spent decades playing out that pattern. I summarily rented an apartment the day I turned eighteen, somehow assuming that’s just what you did as part of growing up—separate and make your own way. It’s no accident that I’ve had thirty-six home addresses in sixty-four years.

Recently, however, I’ve been sharing my own life stories with readers, with my family, and with my kids. The more stories I recall, the more questions I run up against about my own past. I’ve turned to my parents for context and over time, I’ve begun to see the significant influence that family of origin has on one’s perspective. Which led me to seek conversation about a family history I’ve ignored for more than half a century.

My mother’s furrowed brow relaxed once I gave her permission to be an observer, but within ten minutes she had forgotten that she had dementia and that her memory is completely shot as she’s wont to remind us these days. Suddenly, she was weighing in.

“My parents’ first dates were in a graveyard behind the hospital where they both worked,” she recalled. “Employees were forbidden to date, so they had to meet in secret on their breaks.” I found myself contemplating the volume of affection my grandparents must have had for one another to overlook countless tombstones and imagine a bright future despite the visual reminder that we all have an expiry date.

Chiming in regarding his own parents, my father remembered that my grandma Jenny poorly returned a tennis serve that struck my grandfather in the head as an accidental, though oddly serendipitous, means of introduction. And here I am—alive today because my grandmother was a questionable tennis player.

I took notes while my mother and father in turn traded stories about their parents’ lives. Pauses in their narrative was my cue to keep the questions flowing. How many siblings did their parents have? Did they ever meet their grandparents? What were their early memories of holidays?

By the time my brother’s family joined us for Christmas dinner we’d logged a few dozen stories.

“Can we do this every week for a while?” I asked. Rather than looking daunted by the prospect they both seemed enthusiastic and agreed.

My brother surveyed the table and began rummaging through other nearby boxes of memorabilia.

“Where’s the book?” he queried.

“What book?” we asked.

“There was a red book of grandma’s stories we used to have. Mom wrote them down a long time ago.”

We fully searched the dusty cardboard containers for the mythical book, but came up empty handed.

It wasn’t until the next day that it occurred to me the book might be close by. I decided to brave the teetering stacks of stored items in the backside of our garage, just in case I somehow missed some family treasure that got buried in the chaos of two moves last year.

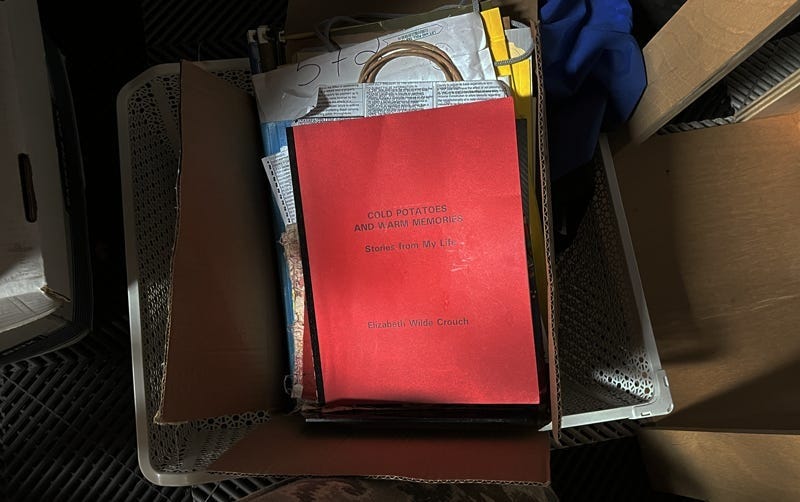

Lifting a box of old Archie comics off a stack of crates revealed a couple of throw pillows. Turning them aside, I discovered a long-decayed mouse carcass stuck to the bottom of the larger cushion. Directly beneath it, I found myself staring at a soft-bound red paper cover that read . . .

“‘Cold Potatoes and Warm Memories,’ by Elizabeth Wilde Crouch.”

My mother had absolutely no recollection of this. She had interviewed her mother Betty almost thirty-five years ago and turned those conversations into a 20,000-word collection of life stories. Just two weeks ago memories of my grandmother had surfaced in my mind and I wrote about some of the indelible moments that remain with me. Now, holding these new stories in my hand, she was reaching back through time with more to give.

Through the book, I learned that my great-great-grandfather was a wandering artist, violin maker, prolific painter, and gold prospector who chased mining claims during the California gold rush and then gambled his fortunes away while making his way home across the country.

His son, my great-grandfather, was known for his minstrel shows in the villages of turn-of-the-century New England. Betty describes him as a storyteller extraordinaire who in the process of “throwing the bull” would convince even himself of the truth of his fabrications. He was a good man whose character unraveled later in life, becoming irresponsible with the family finances and leaving other family members to pick up the pieces.

Betty’s husband, my grandfather Everette Crouch, was essentially disowned by his mother in a circus of seventeen children. Yes. Seventeen brothers and sisters from the same mother. He was one of two children that the Crouch matriarch deemed expendable. Basics like food and clothing were not evenly shared or distributed to them and they were left to scrap for these essentials on their own. It was this same grandfather who stepped into my grandmother’s clan after their marriage, working multiple jobs to cover debts, right wrongs, and help care for his ailing mother-in-law.

It was Betty’s grandmother that made the greatest impression on her. Betty wrote:

My grandmother Eyers was a person who was a big influence in my life. I just thought the world of her. She had a lot of patience, and I always said that I hoped I could be the same kind of grandmother to my grandchildren that she was to me.

Betty’s demeanor was a choice she had made as a child after sampling her own elders and carefully selecting the role model that inspired her, that demonstrated a manner she wished to replicate in the world. I was unquestionably the closest to my grandmother, and now I was learning that the exceptional quality of her attention was not a roll of the dice, it was a decision.

I read some of my grandmother’s stories to my wife before bed last night and woke up the next morning with a dream fresh in my mind.

I’m walking through an old-time village and marveling at the simple beauty of a tree-lined avenue: shops and store fronts, as well as bay windows on Victorian homes with white feather beds visible through the curtains. It was as though I was looking through the eyes of a child, unburdened by any weight of the past or any hope for the future.

Suddenly, I realized that I’d left my backpack somewhere in my travels and that with it, I’d lost my phone. An anachronistic pairing of course, but there on that village street, I felt a great sense of relief and unburdening, utterly content with the experience of the moment and nothing to distract me from it—pervaded with a sense of wholeness.

Half in the dream and half in real life, I gradually woke up in my real bed, luxuriating in this deep sense of completeness that came from connecting with my ancestry.

My grandmother’s stories revealed that I was heir to both greatness and a paucity of character across the generations. Some of my forebears were favorable and virtuous, and others marked our name like a stain. There was heartbreak, disappointment, illness, lost opportunity, and relationships that missed the mark. Yet putting my attention on the full breadth of these people who had come before in my lineage revealed the substrate of love that lies at the base of humanness.

When one’s family is taken as a whole, embraced in its entirety through its stories, this foundation of love is revealed; not as Hallmark memories or Norman Rockwell moments, but in the unconditional embrace of the complete familial line.

This was new to me, this sense of ownership, of belonging. I was being made whole by this line of people who were inspiring and flawed and kind and struggling and heartbroken and brilliant and talented—all at once. From separateness to being part of a continuum.

Family is no longer what I thought it was, a practical matter of births and deaths.

It’s a spiritual arrangement that’s designed to initiate us into the truth of no-separation. And it’s the specific collection of personalities and dramas and love and traumas and affection we’re assigned that, by design, has the potential to initiate us into unconditional love.

Unconditional love doesn’t belong to the person who always manages to be kind to you. It is dispensed by the stars above and the rocks below. And if we’re willing to say yes to the whole blessing and catastrophe of human experience, love finds us in the hurricane and we feel blessed by the hundred mile an hour winds as well as the flower that buckles, bends and shines like a jewel in the gale.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on family stories. Have you collected any over the years? Do you have parents or grandparents still living who might be willing to answer questions about your family history? How important is it to you?

Many thanks to my writing community at Write Hearted and especially Larry Urish Kathy Ayers and Skip Lackey for helping me sort my thoughts and experience on these recent events and distill them into this essay.

“You are not a drop in the ocean; you are the entire ocean in a drop.” — Rumi

Amazing to find that precious red book, Rick, joining so many dots and full of fascinating family history. And your mother having no memory of those interviews with her mother. What a springboard.

I was grateful that years ago a member of my dad’s church met with him and wrote down his stories about his Yorkshire childhood and youth each week for the parish newsletter, some of which I’d never heard before. I read a couple of them at his funeral and they capture his voice and a time in history so well.

I’ve inherited one great grandfather’s diary, another vivid piece of family patchwork.